READING TIME 60-90min

- Intermediate Level

- Individual quiz activity and group discussion

- Pen/Paper, Post-its, Computer Text File

While research is often thought of as an academic exercise, it is an integral part of design → development. The depth of your research often correlates to how effective your tool or service is. The richness of this research is largely determined by how close you are to the communities you’re working with and how well you listen to them. The type of research and research methods you select can vary widely depending on the tools and services you are creating.

This chapter gives background on research methods and terms, how to safely engage in research, and outlines how to get started with your research.

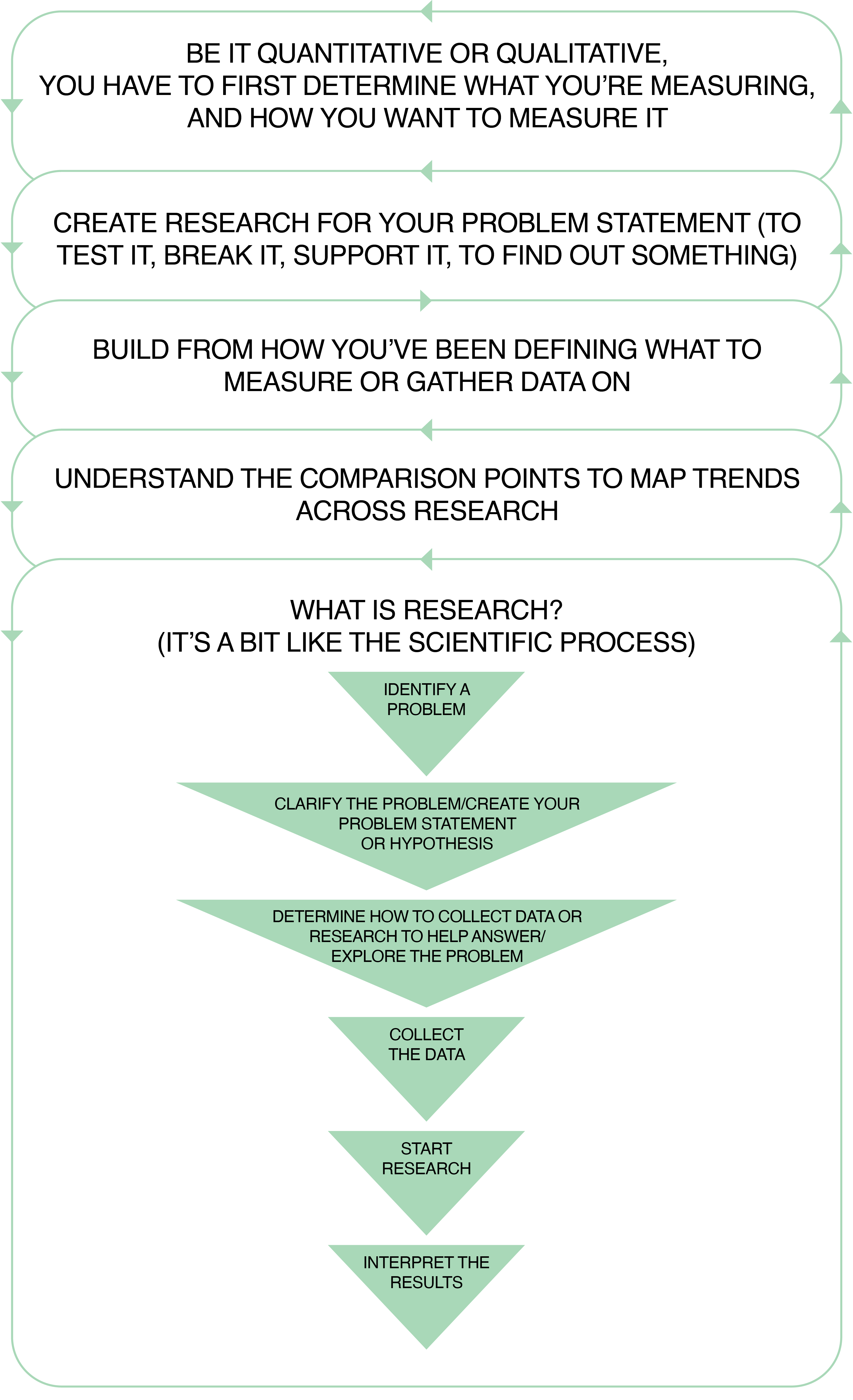

Research provides a holistic view and understanding of the problem you are solving. It can include quantitative research (numerical data, statistical analysis) and qualitative research (talking to people, firsthand accounts, desk research, and environmental scans to understand what literature/research already exists). Using a HRCD approach means combining different types of research and deeply involving the community to ensure your own biases, wants, and desires are not overpowering the research process.

Statement we’ve heard repeatedly when working and collaborating with organizations is that ‘they want to do research but don’t have enough time.’ This often resonates with a lot of people. Small organizations may have limited capacity to complete research and need to move to market quickly. Bigger organizations may rely on one department to do the research and don’t have consistent strategy, or budgets, for research across their teams.

While it’s true, doing good research takes time and resources, it is necessary for all decision making. To have a design process that focuses on equity and inclusion you must dedicate a lot of time for research. Deep research is the most effective way to center the community and understand their needs, concerns, risks, etc. By not engaging in research you risk creating unneeded or, at worse, harmful solutions.

Move Slow and Learn Things

A HRCD research process centers on user research and moves at the speed of users which accommodates their prior experiences and their needs. It’s critical to move at the right speed to build trust between the users and researchers.

Remember that you not only need user research, but also in-depth knowledge of the domain. When conducting research, focus on the goals at hand. Important questions to ask yourself include:

Are you just doing research for the sake of research? This can have its merits, but can also remove the needs and realities of the people related to the area you’re looking at. Are you doing preliminary or initial research or desk research to broadly understand a problem and a problem space? Are you intending to build something? Do you know if you need to build something? Are you validating pre-existing research, or are you trying to develop insights for an advocacy campaign? Who is involved in the research process?

One key way to center the community is to engage in community or participatory research. Participatory research involves the users or communities in the design process as equitable collaborators. Many groups, researchers, NGOs/CSOS, and companies often say they do participatory or community based work, but they are only superficially engaging with communities without going deeper with them into the design process. To truly be participatory, you have to equitably engage with the community or users within the problem, topic, campaign or research you’re exploring. In community research, you can work alongside a group of people to collect their experiences and data to gain insights and learn trends in a deeper, and more focused, way.

There are two primary types of research:

Quantitative Research: Gathers numeric data to discover numeric patterns that attempt to establish cause and effect relationships among the variables. By collecting quantitative information, researchers can conduct a wide range of statistical analyses (both simple and sophisticated) to show relationships among the data (e.g. relating the zip code where you were born to your maximum earning potential), or across the data (e.g. Russia has the same GDP as Spain). Quantitative research includes surveys (with a large amount of participants), A/B testing, analytics (in online and offline spaces), and others.

Qualitative Research: Allows researchers to gain deep contextual insights into a person’s lived experience using non-numerical means and direct observations such as through interviews, text, video, and audio. Qualitative research involves observations, user interviews, and a variety of other methods to help one better understand those they are working with. Oral histories of firsthand accounts provide context for and relay nuanced details about an event they’ve experienced, which helps researchers form and validate (or disprove) their hypotheses.

Commonly used in ethnographic research, and foundational for HRCD work, it helps to unearth people’s lived experiences, attitudes, behaviors, and hidden factors that can lead to more responsive designs, and, ultimately products or services aimed to help a specific community. It often adds more ‘color’ or detail to what we are trying to measure with other forms of research.

Quant vs. Qual

Quantitative research includes methodologies such as questionnaires, structured observations or experiments and stands in contrast to qualitative research. Qualitative research involves the collection and analysis of narratives and/or open-ended observations through methodologies such as interviews, focus groups or ethnographies.

Qualitative research often reveals a more nuanced context, hidden details, and sometimes, users’ solutions to their own problems, whereas quantitative research often merely identifies the problem but lacks key context or details that will help you solve it. In the context of HRCD, qualitative methods are extremely important as they enable researchers to gain deeper first-hand knowledge of a community’s challenges and issues and immerse researchers into the environment.

Quantitative research is frequently used alongside qualitative research to help paint a more complete picture of whatever is being measured. This is called mixed-methods research. For HRCD, we recommend that if you perform quantitative research, you also engage in qualitative research that center’s people’s experiences to ensure you are getting a well-rounded account of people’s lived-experiences and needs. For example, let’s say you have a project seeking to better understand the needs of a community and how a tool may or may not meet those needs. You may send a questionnaire asking community members to indicate pain points they face on a scale from 1 to 10 (quantitative). To supplement this questionnaire, you may conduct in-depth interviews with multiple community members and ask them to explain those pain points more deeply. This can help surface disparities across users and provide deeper insights that a number on a scale may not reveal. We dive deeper into mixed-methods research later in this chapter.

While there are many methods used in quantitative research, the following four are the most common:

- Surveys and questionnaires: gathering insights for what problems people face, what kinds of tools they use, how they use things, really anything.

- A/b testing: Testing how people understand or respond to or use more frequently two different kinds of products/designs/etc. For example, you can a/b test a data visualization to see what people enjoyed more and which was more readable and legible

- Analytics: Seeing metrics, for example, where are people on your website or product, where do they disappear, what do they click on. This is especially useful for interaction design and product design

- Desirability studies: Measuring the aspect of your product on an aesthetic level, and asking participants to select from description words. This can help draw powerful insights from your designs.

For more information about types of quantitative research, check out these resources:

Like with quantitative methods, there are a number methods used in qualitative research. We highlight some common methods that are useful in the context of design → development:

- Diary studies: Users document their activities over a period of time. This gives researchers subjective, context-rich information about users;’ authentic feelings and observations in the moment as events unfold.

- Structured User Interviews: Asks users specific questions and analyzes their responses.

- Semi-Structured User Interviews: Asks more open-ended questions that allows for a free flowing conversation.

- Participant Observation: A researcher embeds themselves in a users’ environment to watch the users’ day-to-day behaviors and practices in order to learn what users’ lived experiences are like and how they respond to them. The researcher observes, notes, records, describes, analyzes, and interprets users, their interactions, and related events in order to have a holistic report of behaviors and beliefs of a given user, community, or organization.

While some of the following types of research may be a subset of quantitative or qualitative research, it is important to familiarize yourselves with these method types!

-

Desk Research: Often called secondary research, desk research refers to research you can perform at your desk. Desk research is a broad term but is more like a literature review where you are finding and collecting publicly-available research like published reports, articles, etc., on your topic.

-

Descriptive Research: Helps better define an opinion, attitude, or behavior held by a group. It often looks at pre-existing research like surveys, information from studies, panels and observations.

-

Causal Research: Looks at cause-effect relationships or preferences. This can use experiments (like a/b testing) to help unpack research.

-

Exploratory Research: Helps uncover insights and ideas, and can use surveys, case studies, and qualitative interviews.

-

OSINT: This stands for ‘open source intelligence’ and includes combining multiple kinds of data: public documents, information about how technology is built, information from social media, and any other publicly available information you can think of! Examples include: Bellingcat, Mnemonic’s Syrian Archive, UC Berkeley’s Human Rights Center, and many more.

Landscape Analysis: A Key Aspect of Desk Research

This method includes blog posts from activists, firsthand accounts, journalism articles, investigations or articles or comments from think tanks, advocacy groups and NGOs, and academic articles. This is incredibly key (and it’s something you should have done extensively BEFORE you started coming up with your idea, engaging in a topic or approaching communities). Sam Gregory, a lead at Witness, reminders us that often activists, advocates and communities are time stressed and capacity stretched, so before you go to them with a question or a comment, make sure they haven’t already documented it in a blog post, written about it in a article or covered it in a research talk. This advice extends really well to research: engaging in extensive preliminary research (and ecosystem mapping that we highlighted earlier) is a key part of HRCD because it grounds you in the problem, and lets you see the complexities of it, without wasting anyone's time.

Usability testing is crucial when designing and developing tools and services. Usability can be conducted in-person or remotely and includes the following testing methods:

-

Moderated Testing: The moderator observes and engages with the user while the user is interacting with a product. The moderator can ask in-the-moment questions (allowing for deeper probing), respond to users’ questions and feedback, and guide the user through the tasks.

-

Unmoderated Testing: This form of testing is not moderated or guided. The only person present is the contributor/user who completes predefined tasks and answers predefined questions at their own pace, on their own time and at a location of their choosing. Unmoderated tests are less time-consuming and more flexible than moderated usability tests as users can do them without disrupting their daily workflow.. However, they require careful planning of tasks and potential outcomes and questions as there is no live moderator. A/B testing, surveys, and diary studies are few examples of this type of testing method.

-

Guerrilla or Hallway Testing: This is a fast and informal way to test ideas, to get high-level feedback, and potentially uncover user experience problems.. It can be done anywhere, takes about 10 minutes, and should involve around 8 - 10 users.

Insights from a Community-Led Roundtable

In preparation for writing this project, we held a roundtable on research that included individuals focused on activist and community-led research. Attendees were design and equity-focused practitioners including Fei Liu, Liz Jackson, Matt Bailey, Alex Haagaard, and Francis Tseng.

During the event, Francis recounted a time when he was working at IDEO on a project with a goal of understanding the behavior of employees at grocery stores. The team was running out of research time. Due to this time constraint, a handful of researchers decided to spend roughly six hours inside of a grocery store shopping and used this as research to then guide their design process.

At first glance, using the remaining research time to observe behavior in-person seemed logical, but when we think about this critically it has some flaws. In a practical sense, what you experience as a shopper is very different than what employees experience. In this observational scenario, the researchers are forced to imagine what the employees feel and experience, which erases the employees’ voice and true needs. One day of research is also very limiting, as it doesn’t provide for variants or external impacts that might change the situation in the store. Stepping into someone’s life for one day doesn’t capture all of the frictions and needs that users have. Additionally, researchers wouldn’t be able to understand the different problems faced by different kinds of employees. From an intersectional standpoint, the observational research conducted did not allow researchers to understand different issues due to race, gender, disability, and even job roles. Addressing these problems is best done in a safe space through direct communication on these topics with the employees.

In thinking of Francis’s example, it’s important to consider what research practices would have yielded a more thorough understanding of the employees’ behavior. These can include elongated research processes that are held over a period of time or through recurring events. Instead of solely using observational research, you can use multiple methods of data collection including interviews, focus groups, surveys, etc. and other qualitative methods mentioned above to better understand the true needs and challenges your community faces.

When beginning the research process, you are building relationships and engaging with different communities who have experience and expertise about the problem you are tackling. HRCD engages in a human rights-led participatory design, research, and building process. While participatory design is currently one of the best ways to create more ethical projects, it has room for improvement.

Some critiques of standard participatory design:

- it is not participatory enough;

- participation is too shallow; and

- it alienates the communities because the process uses jargon, structures and examples only known to designers or the organizers of the process (as highlighted by the Design Justice approach.

HRCD participatory design differs in that it insists on building on many years of relationships that center the communities. HRCD’s participatory process cannot be condensed or shortened; it has to be equitable and built on foundational and real relationships with communities.

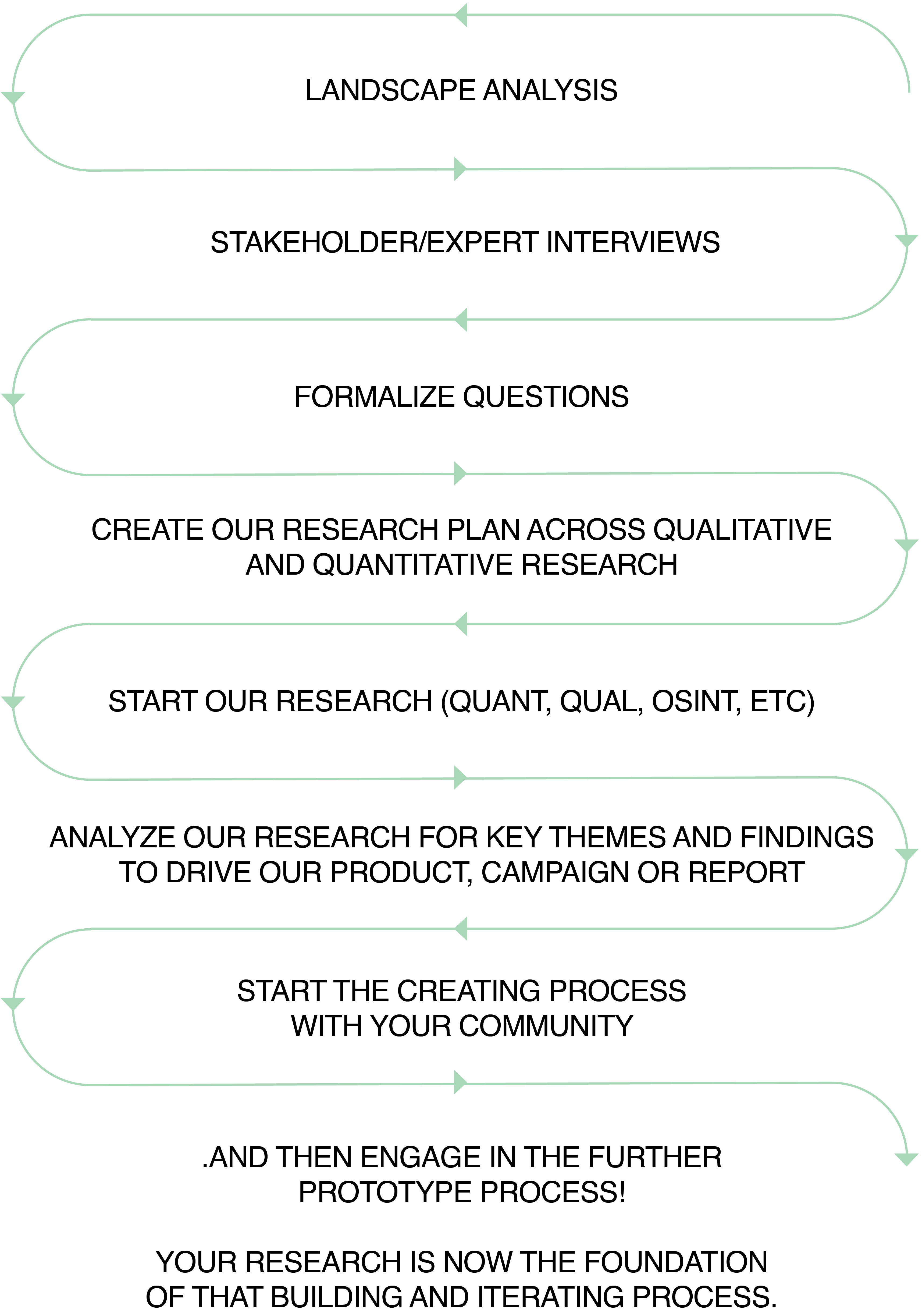

For participatory design, we use this general flow:

- start with preliminary research, like your landscape analysis

- identify and conduct stakeholder/expert interviews

- understand issue and problem areas

- create a research plan across qualitative and quantitative research

- start your research (quant, qual, OSINT, etc.)

- analyze your research for key themes and findings to drive our product, campaign or report

- develop an hypothesis and potential solutions

- test ideas with stakeholders

- conduct research, receive feedback, and iterate

- continue until your product is complete!

To truly engage in human rights centered design, you have to take a mixed methods research approach. Mixed methods is exactly what it sounds like! It means using qualitative, ethnographic, quantitative research, OSINT, along with participatory research, landscape analysis, and firsthand accounts. What specific methods you use will depend on what you create, but it is imperative to do qualitative research to help ground and center the work in people’s real life experiences, needs, and wants. Quantitative research can be helpful when gathering large data points to help inform your work. Sometimes, the qualitative research helps inform the quantitative and vice versa.

Tips on Conducting Mixed Methods Research

Starting with problem statements Starting with a problem statement or question is important as it helps you define what you’re researching, building, or creating around so you can draw parameters within that research and comparison points. The goal is not to be too broad or too narrow. It’s a delicate balance of ensuring you’re creating work that is intersectional and speaks to a variety of different people, but also isn’t too broad to where your community’s voices get lost.

People’s needs can be both complex and straightforward. Our research should gather their lived experiences and capture the nuances in the harms they face. Asking if someone experiences types of harm, such as harassment, can easily be a yes or no answer. Understanding how much harm, where it happens, and how it impacts them allows for a deeper analysis that lets you map how harassment impacts different groups of people and allows you to compare the multi-layered dimensions.

Employing Security When Researching

As discussed in Phase I, to connect with your community it is imperative you communicate with them in a safe and secure way. It is no different when you are conducting research. It is important to conduct surveys, interviews, or observations on/over secure channels where the information collected will remain safe.

When choosing a platform to use, consider the following:

- Does the platform have open source code so you, or experts, can ensure the code hasn’t been tampered with?

- Does the platform provide end-to-end encryption?

- Is it hosted by a third party or hosted locally which enables you full control over the data?

- Should you use a VPN when using these tools / channels?

- Who has access to the tools and the data?

- What types of personally identifiable information does it store of your interviewees?

Qualitative methods and ethnographic research methods can provide you with more detail about a situation or an answer because it combines observation and real time engagement with a person or community. In a survey, someone may just say ‘no’ in regard to not using a particular app but qualitative research gives you the opportunity to understand why they don’t use a particular app.

An example from our research

When co-author Caroline was researching harassment against journalists, she noticed some journalists and bloggers from China and Iran were using Telegram to communicate, often citing that it felt safer or more secure. Telegram is often considered ‘insecure’ by Global North researchers since the engineers will not open source their code to be audited.

“In an interview in 2019, Mahsa Alimardani, an Iranian Internet researcher working with Oxford Internet Institute and Article 19, helped better contextualize how Telegram’s design can provide security via the design of the chat app, even if its software isn’t as secure as Signal. Alimardani explains, "If you spend time going through case files of arrests in Iran, the majority of the time you find the arrests are based on public social media posts or evidence gathered from seized devices. How good the encryption on the chat app you used won't be of much use in this scenario. Destroyed logs of chats will.'' For example, one of the interviewees from China said, “But Telegram, you have to use the V.P.N. to use Telegram. The fact of inconvenience just makes you feel like the Telegram is more secure, like the government has no way to control it, so they just banned it. It just makes me feel like this app...maybe is more secure than others.”

In this project, a combination of qualitative research, and expert interviews helped elucidate why Telegram was being used and perceived in a way that quantitative research, like a survey, could not have uncovered.

On Conducting Qualitative User Interviews

Think about what you are measuring. How will the questions get you there?

- Ask more open-ended questions that let the interviewee share their experiences to avoid leading questions that might impact your results.

- Ask situational questions in regard to the data you’re collecting. If you are researching eating habits, ask questions like: how did you make dinner last night? What’s your favorite meal to make? What meal do you cook the most?

- Measure how, why, and what a person does and when they do it in response to your question. This can be sentiment to the product or question (what they like, dislike), frequency of use, environmental uses, and what they would like to change.

- Look for use cases or examples for your problem statement. These use cases don’t have to support your problem statement, it can disprove it or complicate it.

- A big reason for qualitative interviews is it helps us check our assumptions about the problem we are researching and solving. It can help uncover why something is happening. Ask questions that get at the ‘why.’

- Prepare for the interview by designing a script, which is a series of questions. These questions are to help you answer your problem statement and measure or map aspects of your data. For example: asking what someone's favorite meal to make answers a different kind of question than what meal they make the most. One question focuses on enjoyment, and one focuses on ease of creation. You can then follow up by asking why they make that type of food so frequently.

Setting up a Qualitative User Interview

Through this process, you, as the interviewer, will create a script of questions to ask different interviewees. You are looking for insights not explored in depth during a survey such as more nuanced details about the who/what/why/where/how of their needs and workflows. This is where you can ask follow-up questions, clarifications, emotional responses or observations. By interviewing different users, you can gain more broad insights and compare their responses to look for patterns. You can also compare an individual interviewee's answers to other answers they’ve given in different formats. For example, comparing answers they’ve given on surveys versus interviews to look for consistencies/inconsistencies and discover, sometimes unsaid, ways you can help them solve their problems.

General Qualitative User Interview Tips!

- Be Empathic: Conducting an interview is not just ‘walking in someone else’s shoes’ but really trying to understand how they are making decisions and why they make them. Using empathy will allow the research to better understand the environmental reasons, cultural, personal, and political reasons surrounding their decisions.

- Active Listening: So much of user interviews is deeply listening to someone and their answers. They may say something that complicates your problem or adds more depth and value which will require you to dig deeper on that specific topic. With active listening you are not just hearing what you want to hear but hearing what the person is telling you.

When working with victims of workplace harassment, it’s important to be really careful about how we talk to victims. Asking a question like “how do you know this was harassment” can be perceived as gaslighting but most importantly, can upset the person being interviewed. It’s important to build trust with the people you are talking to and understand how, or why, their rights have been impacted. They may not have a deep understanding of human rights issues or historic practices in their location, community, or culture. However, they will at the very least have an understanding of how they feel and the impact it has on them.

In this exercise develop a script for how you will create a safe space for the person you are interviewing to share their experience. Note what type of information you will provide to make them feel safe while telling the story, how you will ensure that their information won’t cause them further harm, and what you plan to do with the information they share. This script can be used as an introduction when speaking with future interviewees.

For this exercise imagine you are interviewing individuals about their methods of transportation.

Ask yourself:

- How does your research, outreach, or threat-modeling change when you change one aspect of your ‘intended’ users’ identity? For example, you switch to working with young women versus older men, or young women who are queer in a more religious country, or young women who are queer in a religious country that do not speak your language and use different cellphones than you do.

- How will they use what you are creating?

- What would you change given the differences between these groups?

- Would you ask different people different questions?

- What are the different safety concerns facing each group?

- How do you then account for their safety?

Qualitative user interviews are a great way to learn more about the context of how users interact with your product, campaign or story, and more details about their daily lives. It’s important to build rapport with a user but remember, this isn’t a conversation, it is an interview.

When interviewing, this nine step process is a helpful roadmap to keep you on track during your interview:

- Begin the interview with “get-to-know-you” questions to build a rapport between everyone present.

- Document the information shared during the interview, either recorded (in a secure way) or by taking notes as you go.

- Use active listening techniques to ensure you capture all the needed information and ask the most appropriate follow-up questions.

- Watch for body language cues that may share when information is sensitive, trauma-inducing, or uncomfortable.

- Use interviews to gather more information or expand upon answers, by using questions or prompts like:

- Tell me more about that.

- Can you expand on that more?

- Can you give me an example?

- How did you feel about that?

- Tell me more about that or what motivated you to do that?

- Why was that important to you?

- Pivot questions as needed if the information they share leads you towards new ideas / solutions. I.e. If a new pain point or need arises during your interview, explore this as it will be useful before you begin designing your product or service.

- Acknowledge emotions and tone in your notes.

- Avoid interrogating questions that could intimidate others and make them feel less comfortable sharing information.

- At the end of your interview, be sure to ask if they have anything to add that you may not have covered.

Sample Script:

Hi there, thank you so much for trusting me with your story. I can give you a little bit of background about the project. I am __, and I am working with ____. Our project is __(give a few sentences about the project you’re working on).

For our research, we will be using these interviews for**__** (Describe what you are using the interviews for! Is it for a report, an article, or just for background? Be up front with the interviewee). I will be the only one having access to this recording and the transcript will only be made available to **_** for writing purposes. After our report is published, we will be deleting and destroying the transcripts and recordings.

For our interview, how would you like to be cited? Would you prefer to be mentioned by name, cited anonymously, or be interviewed under ‘transparent opacity’? Transparent Opacity means we are not going to be use direct quotes, instead we will reference things you have said, removing all parts that could identity you (like your workplace, exact names) and by only referencing your name instead of direct sentences, this way your style of speaking cannot be pinpointed and you can’t be identified.

(Lastly, add a note here about your project. What are your intentions? Why is speaking to them important?) If you've experienced workplace toxicity or harassment, we would love to hear about it. We're also trying to figure out where the pain points are inside of people's workflows. Is it the combination of a lack of structure plus digital tools plus a lack of management? Is it a combination of these tools just aren't good enough? So, is that leading to frustration? It’s okay if the answer is a variety of different things. For example, using a Trello board to document a research project, that board may look smaller than a board where it's a bunch of engineering tasks that need to be done for example. So, it can sort of skew the idea of productivity. We're trying to measure all of that.

Also note, feel free to mention names and workplaces if that makes you feel comfortable. We will be removing these, and absolutely not referencing them. So don’t feel like you need to self-censor here unless that makes you feel comfortable.

Can we start the interview? Is it okay if I record? It’s just for my notes and for this transcript, and no one else.

Sample Questions

Can you tell me, high level, what happened, or what is an example of harassment or toxicity you’ve faced?

(if not mentioned explicitly, ask kindly “do you think or feel some of this harassment or toxicity is related to your perceived identity or identities?”)

How long have you been remote? Since the pandemic or before?

Do you mind sharing your level, your role, and the size of your company and what it does? We won’t be sharing these details, but it’s helpful for the report to have this data in. For example, if you work for a high school, we won’t say the name but we’ll say, ‘educational institution’ and we’d do the same for colleges, middle schools, etc.

(if there is harassment related to their job title, or a misconception about their job, or a stereotype tied to their job role, they will sometimes mention that around here. But be aware throughout the interview, this is a question or a prompt if you sense is unfolding, that you can ask. Meaning, if they mention confusion over their role, be sure to ask about that like “Who is confused about your job role? Is your boss or teammates confused about your job role, or someone else? What do you think led to that?”)

Is this harassment/toxicity regularly occurring? Or are there other things that have happened? Would you mind sharing some other examples?

This may be a strangely worded question. We've been thinking of the best way to say it. It's a question where it's like could you tell us almost tactically or forensically what happened in a sense of we were talking, so we were messaging on Slack and then my boss did X and this was part of a bigger issue that also the majority of our communication was over Slack. Using that as an example, we're trying to also get a sense of how microaggressions can play out over the phone or over digital tools and trying to think of potential anonymized examples or use cases again, of these forms of aggression, toxicity. I would say in your case it's probably like well over a few years the same things kept happening, but they happened over a few years on these places.

The question I'm going to ask, this is what we ask generally everyone, and I tend to ask every harassment victim this, is has there ever been a moment you wish something existed when you were in the middle of being harassed or trying to report something or document something, it could be a policy, a piece of tech, a product, something, it could be a universal stop button, but is there something you've wished that has existed... And maybe think of a moment or a series of moments when you've been in the middle of a toxic interaction or something involving harassment where you're like oh, I actually really wish I had X. And that could also be someone to advocate for me or someone that knows what I'm doing.

Is there anything else you’d like to share with me or tell me about your experiences, or what has happened to you?

Does your workplace offer grief periods, time off for mental health, mental health resources or other kinds of support? And have you felt comfortable to take those?

What are you doing for self care?

Ending Statement: Thank you so much for your time, I really am honored you have trusted me with your story. I’m so sorry this happened to you but thank you for sharing this with me.

Reflections from Neema Iyer

The following excerpt is from an interview with Neema Iyer, design and research expert, and founder of the NGO, Pollicy. In it, Neema discusses the challenges her team faced conducting research including reaching communities in rural areas and meeting communities where they are at.

“But these are kind of the other struggles that we have: it's very expensive to collect this information because the community that I mentioned in the project was in northern Ghana. You first have to fly to Accra. There were only two planes. One was a propeller plane, and one was a jet. And then once you get there, you have to drive into the middle of nowhere. So, it's super expensive to meet these people and to get this feedback from people to actually understand what's happening. Because the way that technology was set up, you could sit anywhere in the world and build this program, and dispatch it to the phone numbers, but to actually talk to the people and actually go there and find out what's happening that can be really expensive. And that's kind of the challenge that we have in our projects.

Even working in Uganda…we're trying to engage with people in rural communities and to understand their needs and understand where they're coming from. And sometimes, the questions I get are “what is data” and you're going to teach somebody something about data and AI, they don't really understand the basic concept of it itself. But when you think about just how different and how, how the life experience of the community you're trying to work with is totally different and that you need to take that into account. I know we say that a lot in research, but I don't know if we actually really practice it.

One of the things that I really focus on in my work is trying to get the language issue right, because so many digital platforms are in English or other quite colonial languages. A lot of people can’t engage with it because it's not in a language they speak. But at the same time, for example, Uganda has like 50 official languages, and you just can't do something in 15 languages, because there's no resources for that. So the other thing is literacy, even people who can read, don't want to read. If you are building something, can you make a bit more audio visual, so that they can interact with it? Because, even myself, like, I love reading, but I'm so overwhelmed right now with people keep sharing new articles.

And then the third part is getting community feedback. So, whenever we build something, even before we build it, we bring in a lot of focus group discussions. We invite people who do work with the communities, like community based organizations, or civil society organizations that are quite embedded in these communities and understand them. So those are the kinds of people that we invite, and then we showcase what we're working on, or we ask for their advice. And they 've built quite strong networks over the past years. And so, whenever we invite them, they actually do show up and they do participate, and they give us feedback, which based on the fact that they work with these communities, we find it quite easy to incorporate into what we're building.

The main part is kind of doing iterative research to figure out whatever you build resonating with your community, trying to reach people where they are so either in their languages or at a time that suits them or in a format that suits them.”

A High-Level Recap of the Research Process